In the commercial coffee equipment sector, pump pressure is not merely a static variable; it is the kinetic engine driving the emulsification of lipids and the dissolution of soluble solids. For technicians and distributors, a granular understanding of hydraulic systems differentiates high-performance setups from standard installations. This guide explores the engineering behind espresso machine pump pressure, comparing pump technologies, analyzing pressure profiling mechanics, and detailing maintenance protocols for sustained operational reliability.

Pressure in an espresso context is technically defined as the force exerted by water against the resistance of the coffee puck. It is governed by Darcy’s Law, where flow rate through a porous medium is directly proportional to the pressure drop and inversely proportional to the viscosity of the fluid. In commercial espresso machines, the pump generates flow, and the coffee puck generates resistance. The resulting pressure (typically measured in bars) is the byproduct of this interaction.

The industry standard of 9 bars (approximately 130 PSI) is not arbitrary. It represents the intersection where water density and thermal energy provide sufficient force to emulsify coffee oils into crema without compressing the puck to the point of complete impermeability (channeling). However, achieving and maintaining this pressure requires robust pump architecture.

For B2B applications, selecting the correct pump architecture impacts Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) and cup consistency. The two dominant technologies are Positive Displacement Rotary Vane pumps and Vibratory pumps.

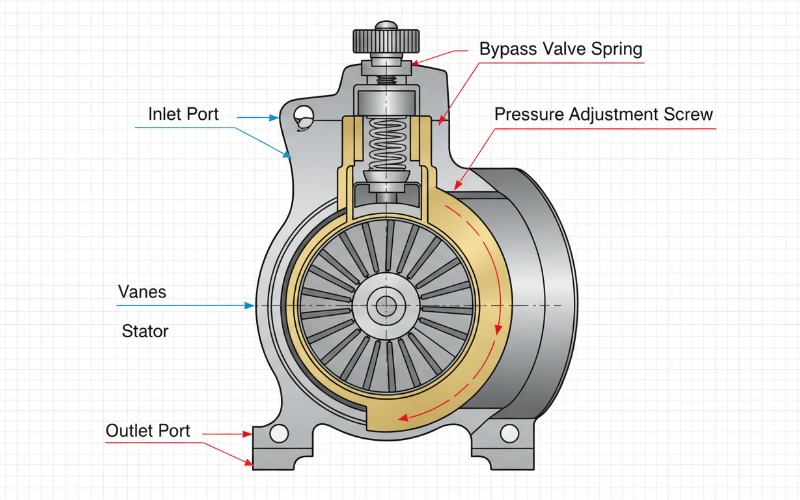

Standard in commercial multi-group machines (e.g., La Marzocco, Synesso, Kees van der Westen), rotary pumps utilize a rotating mechanism with sliding vanes. As the rotor spins, centrifugal force pushes the vanes against the chamber wall, creating expanding and contracting chambers that move water.

Common in domestic or light-commercial semi-automatic machines, vibratory pumps use a piston attached to a magnet set inside a metal coil. When current is applied, the magnetic field drives the piston back and forth.

| Feature | Rotary Vane Pump | Vibratory Pump |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Positive Displacement (Motor Driven) | Electromagnetic Piston |

| Pressure Profile | Instant, Constant | Progressive Ramp |

| Flow Capacity | High (supports multi-group) | Low (single group focus) |

| Noise Level | Low (Silent operation) | High (Vibration noise) |

| Lifespan | High (Serviceable) | Medium (Disposable) |

| Primary Use Case | Commercial Cafes, High-end Home | Home, Office, Low-volume |

In systems utilizing rotary pumps, the pressure regulation is often handled internally by the pump head’s bypass screw. However, in vibratory systems or specific hydraulic layouts, an Over Pressure Valve (OPV) is critical. The OPV acts as a pressure limiter. Since a vibratory pump can theoretically produce up to 15-18 bars of pressure against a blind filter (zero flow), the OPV diverts excess water back to the tank or drip tray once a specific threshold (e.g., 9 bars) is reached.

For technicians, calibrating the OPV is a primary tuning step. A seized OPV can lead to over-extraction, channeling, and potential damage to the hydraulic circuit gaskets. Conversely, an OPV set too low results in under-extraction and sour flavor profiles due to insufficient force to dissolve heavier lipids.

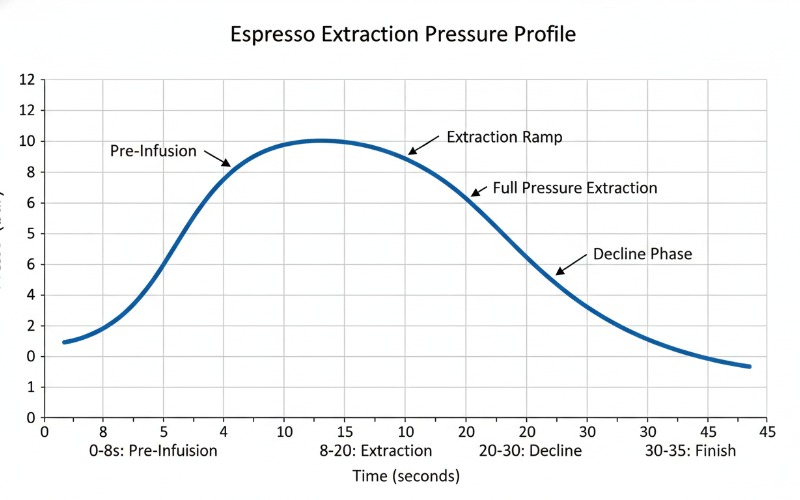

The frontier of espresso technology lies in manipulating pressure during the shot. Fixed 9-bar extraction is giving way to dynamic pressure profiling, allowing baristas to mitigate channeling and optimize extraction for lighter roasts.

Pre-infusion involves saturating the coffee puck at low pressure (1-3 bars) before the main pump pressure is applied. This reduces the risk of channeling by allowing the puck to swell and seal against the basket walls.

While often used interchangeably, these terms refer to different control variables. Pressure profiling adjusts the force exerted by the pump. Flow profiling utilizes a needle valve (often at the group head) to restrict the aperture through which water passes. By restricting flow, pressure naturally drops (following Bernoulli’s principle). Flow control offers more granular management of the “decline phase” of extraction, where the puck erodes and resistance decreases. Maintaining high pressure during this phase often leads to astringency; tapering flow/pressure preserves sweetness.

For B2B distributors and service technicians, identifying pressure-related faults is essential for minimizing downtime.

If a rotary pump is starved of water, cavitation occurs. This is the formation of vapor cavities in the liquid—small liquid-free zones (“bubbles”)—that are the consequence of forces acting upon the liquid. When these bubbles collapse, they generate intense shockwaves that can pit the metal surfaces of the pump vanes and housing. Symptoms include loud rattling noises and fluctuating pressure gauges.

Limescale accumulation in the gicleur (restrictor) or the pump bypass valve will alter flow dynamics. A scaled bypass valve may seize, preventing pressure adjustment or causing safety valves to trip. Regular descaling and water filtration with controlled TDS (Total Dissolved Solids) and hardness buffers are non-negotiable for commercial warranties.

Fluctuating pressure usually indicates either air in the system, a failing pump capacitor (for motor start), or cavitation due to insufficient water supply pressure. In rotary systems, check the inlet water line filter for blockages.

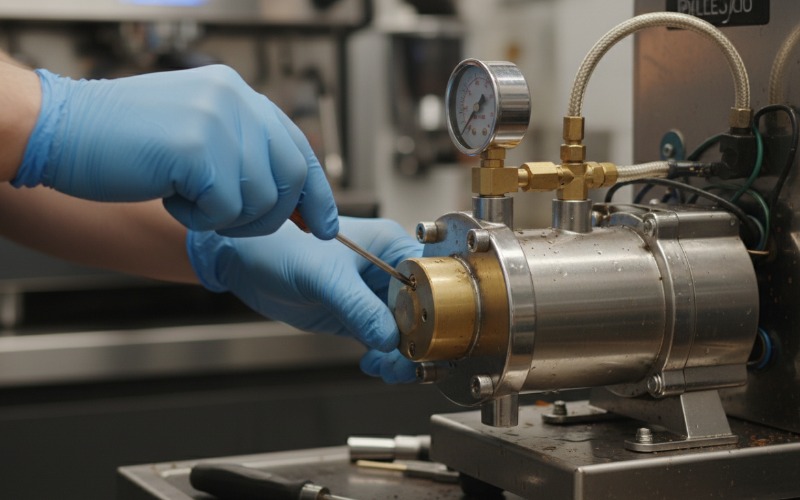

Yes. On rotary vane pumps, there is a bypass screw located on the pump head. Turning it clockwise increases pressure; counter-clockwise decreases it. This should always be performed with a blind filter engaged to read the maximum pump pressure effectively.