For commercial coffee machine engineers and distributors, espresso crema is not merely a visual garnish; it is a vital diagnostic outcome of the extraction process. It represents the successful intersection of hydraulic pressure, thermal precision, and chemical solubility. Understanding the physics behind crema formation allows technicians to fine-tune high-end espresso machinery, ensuring client satisfaction and minimizing Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) through reduced waste and optimized calibration.

To define crema technically, we must look beyond the cup and into the group head. Crema is a stable foam generated when water under high pressure (traditionally 9 bars or 130 PSI) forces carbon dioxide (CO2) out of the cellular structure of the ground coffee. This process relies on Henry’s Law, which states that the solubility of a gas in a liquid is directly proportional to the pressure of that gas above the liquid.

During the extraction phase inside the portafilter, the water becomes supersaturated with CO2. As the liquid exits the basket and passes through the spout into the cup, it returns to normal atmospheric pressure (1 bar). This rapid depressurization causes the CO2 to exsolve, forming thousands of microscopic bubbles. These bubbles are immediately coated by surface-active compounds—specifically coffee oils and proteins—creating a stable colloid.

In commercial machinery, the quality of this emulsification is heavily dependent on the pump type. Rotary vane pumps, standard in commercial units, provide the consistent flow rate necessary to maintain the pressure required for lipid emulsification. Vibratory pumps, often found in prosumer gear, may struggle to maintain the shear force required to fully emulsify the oils, resulting in thinner, less persistent crema.

Modern pressure profiling machines allow baristas to manipulate this phase. By ramping pressure slowly (pre-infusion), the fines migration is managed, but the peak pressure phase (9 bars) remains critical for the physical creation of the foam. If the pressure drops below 8 bars, the emulsification of the lipids fails, resulting in a black, flat beverage lacking the mouthfeel characteristic of espresso.

The persistence and texture of crema are dictated by the chemical makeup of the coffee bean and the extraction efficiency. For B2B suppliers dealing with complaints about “thin coffee,” understanding the chemistry is the first step in troubleshooting.

Coffee oils (lipids) are hydrophobic. Under high pressure and temperature, they are forced into an emulsion. However, oil alone reduces surface tension and destroys foam (think of soap in a greasy pan). The stability of crema comes from surfactants: proteins and melanoidins.

Robusta beans typically produce thicker, more persistent crema than Arabica. This is because Robusta contains nearly half the lipid content of Arabica (10-11% vs. 15-17%) but significantly higher protein content. Lower oil content combined with structural proteins creates a stiffer foam structure. However, the trade-off is often palatability. High-quality Arabica crema is more delicate due to the higher lipid load destabilizing the bubbles, but it carries more aromatic complexity.

The reddish-brown color of crema is derived from melanoidins, complex polymers formed during the roasting process via the Maillard reaction. These compounds are not only responsible for color but also contribute to the viscosity and texture of the espresso. A pale crema often indicates insufficient development during roasting (lack of melanoidins) or low extraction temperature, preventing these heavy molecules from dissolving effectively.

For the field technician, the cup is a data readout. Before attaching a SCACE device or checking pump gauges, the visual appearance of the crema offers immediate clues regarding machine calibration.

Temperature plays a crucial role in solubility. Water that is too cool (below 88°C) will fail to extract the heavier lipids and fatty acids, resulting in a thin, pale foam that dissipates rapidly. Conversely, water that is superheated (above 96°C) can cause the protein structures to break down too quickly and burn the sugars, leading to a dark, charred-looking ring with a large bubble structure (boiling effect).

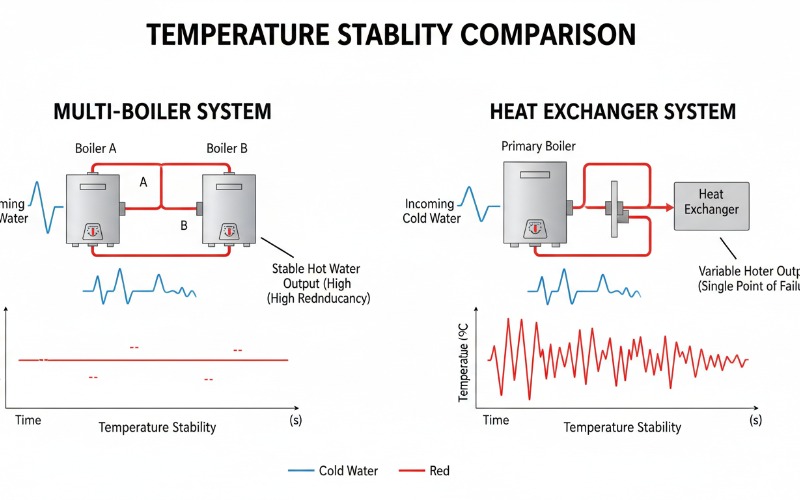

In multi-boiler systems with PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) controllers, temperature stability is maintained within 0.1°C. When a client complains of inconsistent crema, verify the offset settings on the PID and check for scale buildup in the heat exchanger or boiler, which can insulate the water probe and cause erratic heating cycles.

“Tiger striping” or mottling is often cited as the gold standard visually, indicating a rich extraction of solids. However, if the crema shows large, pale spots, it indicates channeling. High-pressure water follows the path of least resistance. If the puck preparation is poor or the shower screen is clogged, water will drill a hole through the coffee bed.

This results in local over-extraction (bitterness) and global under-extraction (sourness), visually represented by a crema that breaks apart. For technicians, this signals a need to inspect the dispersion screen for uneven flow or to check the grinder’s burr alignment (particle size distribution).

The following table correlates visual crema characteristics with potential technical root causes, aiding in rapid diagnosis during site visits.

| Crema Characteristic | Physical Indication | Technical Root Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pale / Thin / Dissipates Fast | Under-extraction / Low Viscosity | Low Water Temp (<88°C), Low Pressure (<7 bar), Stale Coffee (Low CO2) | Check PID offset, verify pump pressure, check roast date. |

| Dark Brown / Black Edges | Over-extraction / Burnt Sugars | High Water Temp (>96°C), Fine Grind, Dirty Dispersion Screen | Lower boiler temp, coarsen grind, clean group head. |

| Large Bubbles (Soap-like) | Turbulence / Boiling | Flash boiling at group head, High flow rate (Gicleur issue) | Check anti-suction valve, inspect gicleur for wear. |

| Tiger Striping (Mottling) | Optimal Extraction | Balanced Pressure/Temp, High fines migration (controlled) | Maintain current calibration parameters. |

| No Crema | Lack of Emulsion | Pump Failure, zero CO2 (Old Coffee), Extreme Coarseness | Check pump capacitor, replace burrs, verify coffee freshness. |

From an inventory management perspective, crema is a freshness timer. Freshly roasted coffee contains high levels of CO2 trapped within the cellulose matrix. As coffee ages, it de-gasses. Coffee that is 30+ days post-roast (depending on packaging) will have lost most of its CO2.

Without CO2, the physical mechanism for foam creation (nucleation) is absent. No matter how expensive the espresso machine or how stable the pressure, stale coffee cannot produce crema. This is a critical training point for B2B clients: equipment cannot compensate for compromised raw material. Conversely, coffee that is too fresh (1-3 days post-roast) may produce excessive, rocky foam that impedes extraction flow, necessitating a “resting” period.

Water chemistry is the hidden variable in emulsion stability. Water with very low mineral content (RO water without remineralization) lacks the buffer capacity and magnesium/calcium ions that aid in the extraction of flavor compounds. Conversely, overly hard water can dampen the acidity but may actually assist in creating a thicker crema due to increased bicarbonates.

However, sodium-softened water (common in generic softening systems) can destroy crema stability. Sodium ions increase the solubility of coffee significantly but can disrupt the protein bonding required for long-lasting foam. B2B engineers must ensure filtration systems are tuned to aim for a TDS of 100-150ppm with a balanced magnesium hardness to support optimal extraction physics.

Not necessarily. While visually appealing, excessive crema (often found in Robusta blends) can taste ashy and bitter due to the high concentration of fines and carbon dioxide. The goal is a balanced, persistent layer that seals in aromatics, not maximum volume.

Pressure profiling allows the barista to taper the pressure at the end of the shot (e.g., dropping from 9 bar to 6 bar). This reduction decreases the energy in the stream, often resulting in a smoother, less aerated mouthfeel but preserving the crema layer without introducing late-stage bitterness.

The cone shape in a bottomless extraction indicates that the flow is converging effectively in the center of the basket. This suggests uniform extraction and even tamping. If the stream sprays or creates multiple cones, channeling is occurring.

Yes. Rotary pumps offer a more immediate and consistent pressure application compared to vibratory pumps. This consistency aids in a more uniform emulsification of oils, typically leading to a silkier crema texture in commercial settings.